|

|

|

| Official Magazine of the Next 15 Minutes | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Power Of Publicity Rocketed Comedian To Overnight Fame

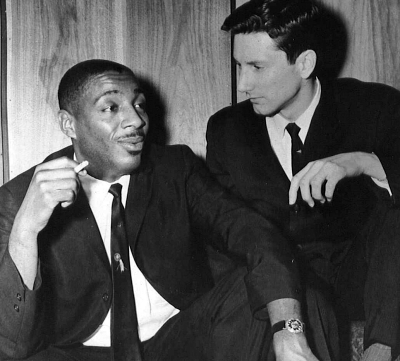

One night on my regular rounds on Rush Street, Chicago’s glitzy showbiz district, I heard gales of laughter coming from the Fickle Pickle, a college hangout. I waved to the owner, ordered a tea (the joint had no liquor license) and listened to a comic I’d never heard before. “Nothing’s free these days,” Dick Gregory was saying. “You can’t even hate me free. Costs two hundred and fifty dollars to join the Ku Klux Klan — and you still got to buy your own sheets.” He had everyone in the white crowd howling. “I sat at a lunch counter for nine months. Then they integrated and didn’t have what I wanted.” Here was a wit a college kid could relish, and these young intellectuals were roaring all through his act. His incisive humor was so captivating that I stayed after the show. We talked late into the night. I told him how fascinated I was with his act, so insightful, that he belonged in the top tier of show business, not in an obscure coffeehouse. He told me how he’d been working all the Negro night spots on the South Side, including the famous Roberts Show Lounge. “But that’s not where it’s at. I can stay there the rest of my life. But I won’t get anywhere and I won’t make any money. What I need is to break into the white nightclubs uptown, like Mr. Kelly’s or the Playboy Club.” “I’ve had plenty of offers from Negro managers,” he said, “but I don’t want anything to do with them.” Mighty strange talk coming from one who claims to speak up for the underprivileged black. “The Negros can’t help me,” he explained. “They don’t know how. All the prestige clubs are owned by the Jews. Negro managers can’t get through the door.” As he saw it, the only one who could help him would be a manager with two essential attributes: white and Jewish. “They’re the only ones who can get me into the top rated lounges. The Negro managers don’t have the know-how or the connections. It takes a Jew to open the door.” In all my wanderings along the nitery circuit, I was unaware that Jews held all the power in the entertainment world. In fact many of the major clubs were run by Italians, Greeks, Irish and others besides Jews. I didn’t care to argue the point with someone steeped in stereotypes. I saw Gregory as the vanguard of a new type of cerebral black entertainer — not the tired buffoonery of Amos ‘n Andy — and I jumped at the opportunity to jumpstart this revolution in American show business.

“We’ll make it together,” he said as we bonded. Money was no consideration; enthusiasm was all. He gave me his word that he’ll compensate me eventually. After all, what could I ask from someone who was making all of five dollars a night at a coffeehouse? Such mundane matters as my fee were deferred for future deliberation. I was excited to promote what I saw was a superstar ready to orbit. That night I morphed from City News Bureau journalist to self-taught publicist. It wasn’t difficult — it just takes chutzpah. Gregory already had an agent, Associated Booking Corporation, headed by Joe Glazer in New York (whose ethnic credentials fitted in with Gregory’s plan). The Chicago office was handled by Freddie Williams, a formidable Irishman. They were able to get Gregory bookings in spots that mostly catered to black audiences. Apparently they did not see his potential further than his home base. I gave up my two newspaper gigs to hang with Greg. Then it happened. The regular comedian at the Playboy Club took ill. It was a Saturday night when the showroom is usually sold out. Victor Lownes, Hugh Hefner’s right-hand man in charge of entertainment, was in a panic. Williams saved the day by offering to send Gregory, a complete unknown, to fill in. Lownes had no choice. As fate would have it, the room filled up with frozen food conventioneers from the South. Undaunted, Gregory bounced on stage and smoothly won them over with his brilliant quips and profound observations of our social ills and prejudices. They never heard wit like this before, especially coming from a black man. Every line drew bursts of raucous laughter. Gregory electrified the audience — he killed! The thunderous applause confirmed my instincts. This man is a star! He belongs on this stage. I can’t let this one-nighter pass into obscurity. This is a break that may never happen again. My heart was racing. I ran to the house phone and asked for Victor Lownes. The operator said sorry, he was not in the club. My heart sank. I insisted she call him at home. I knew I was intruding on his privacy —on a Saturday night! — but I was determined to seize the moment. I held the phone in the air so he could hear the boisterous reaction of these southerners to Gregory’s topical humor. As a Niagara flow of applause flooded the showroom Lownes asked, “What’s his name?” “Dick Gregory,” I said. “You put him in here for one night. You have to come over and see how sensational he is.” Lownes came and looked and booked Gregory for a

three-week engagement. That made me the world’s busiest praise

agent — pushing Gregory’s witticisms (and name) to the Chicago

newspapers on a daily basis. It wasn’t hard when you’re working

with brilliant material. The lines at the club started forming

every day. Lownes was forced to extend Gregory’s show for a

second three-week run, then a third. Every midnight I ran around to the newspaper offices. I was a familiar sight to the night guards as I dropped off envelopes of Gregory’s humorous lines on the desks of the city’s major columnists. Every morning I showed Gregory how the press was promoting his name as the town’s new star. All the columnists eagerly cooperated — actually competing with each other —as they welcomed these items to spice up their columns. The first columnist to break Gregory’s name in print was the Chicago Tribune’s Herb Lyon who enthused, “Hottest and most unusual new talent in show biz is a young Negro comic, Chicagoan Dick Gregory, who works in the satirical manner of Mort Sahl, Bob Newhart and Shelly Berman. He grabs his material from the headlines and is an overnight smash at the Playboy club’s Penthouse.” Irv Kupcinet of the Sun-Times, who loved Gregory’s satirical comedy, said he was the talk of the town. Tony Weitzel in the Daily News tabbed him as the Negro Will Rogers. “In the Congo,” Gregory responded, “they call Mort Sahl the white Dick Gregory.” The intensive barrage of publicity brought out the hard-nosed critics. Their reviews were totally ecstatic.

Playboy’s Hugh

Hefner gave me credit for the cultural upheaval I masterminded

in Chicago. In his introduction to Gregory’s first book,

From the Back of the Bus (Dutton 1962), he described how “a

young, inexperienced, but inexhaustible press agent, Tim Boxer,

badgered a Time magazine writer into watching Gregory

work,” which resulted in a feature article brimming with “lush

praise.” (Hefner admired my efforts to the extent that he

directed Lownes to appoint me his public relations director in

New York for the new Playboy Club and magazine.) The public clamor enabled bigtime New York agent Joe Glazer to get this Chicago phenomenon on NBC’s Jack Paar Tonight Show for his first national TV exposure, followed by a clutch of plum bookings in the uppermost clubs, such as the upper crust Blue Angel in New York and the fabled hungry I in San Francisco. Gregory made it. His dream was coming true. Variety called it “an historic breakthrough in show biz annals” which made Gregory “the first standup comedian of his race to crack the plush intimery circuit, and in such force.” The bible of the entertainment industry went on to acknowledge how I discovered Dick Gregory and made him a star overnight: "Owing to the almost daily raptures of several Chicago columnists, career of young Negro comedian Dick Gregory is streaking off the launching pad like a Canaveral success. Leading the stampede for Gregory, Windy City scribes have shown a virtual mania to “item” the comic, and the result has been a skyrocket that has even blasé tradesters impressed. Consensus is that, for the comparable stage of development, Gregory outcomets Bob Newhart, another Chi product. Comic already has a press agent, however, and almost without saying." Years later at a party in Los Angeles, Bill Cosby thanked me for my efforts on behalf of Dick Gregory, who broke the ceiling and made it possible for Negro standup comedians to follow. Not until I vaulted Gregory to the heights of superstardom were black standups welcome at the sophisticated clubs for the first time in the annals of American culture. As Hefner noted, I was instrumental in helping Gregory become the first Negro comedian to make his way into the nightclub big time. It was a significant moment in the civil rights revolution, little known by the public but acknowledged to me by such prominent African American comedians as Nipsey Russell and Timmie Rogers as well as Bill Cosby. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

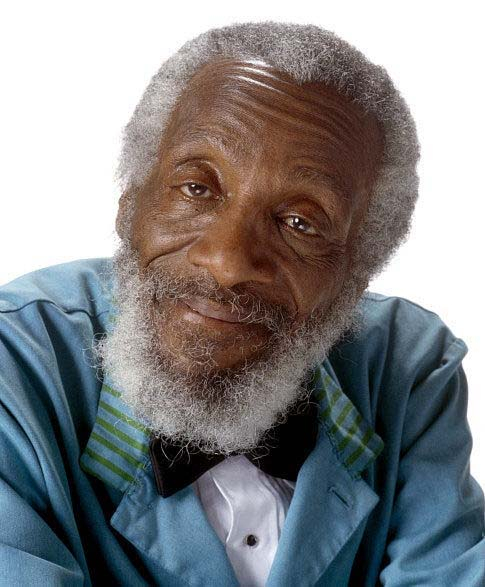

DICK

GREGORY STORY ON STAGE

DICK

GREGORY STORY ON STAGE