Guinness postcard | In Ireland You’ll Find

Guinness Good For You By Sally Ogle Davis and Ivor Davis  ROWING up in Britain, there were a few immutable truths—ideas that were part of the DNA: The Queen was “long to reign over us,” the weather was a suitable opener for any conversation, and Guinness was good for you. ROWING up in Britain, there were a few immutable truths—ideas that were part of the DNA: The Queen was “long to reign over us,” the weather was a suitable opener for any conversation, and Guinness was good for you.

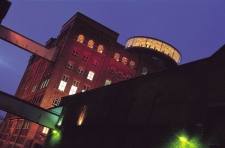

The rich dark brew with the golden creamy head is much more than a drink, especially in Ireland where it is made and where it is one’s entry card to maturity: Down your first pint and, “You’re now a man my son.” They feed the stuff to mothers to replace the iron lost in the birthing process. And the famous Guinness posters are the closest many will ever get to art. So when we landed in Dublin recently, the first port of call had to be the new Guinness Storehouse Visitor Center which, since opening its doors in December 2000, has become the number one tourist attraction in Ireland, surpassing the Blarney Stone, the Lakes of Killarney and the Ring of Kerry. Over one million visitors and counting so far. It’s not difficult to see why. First there’s the building itself. Built in 1904 as the fermentation plant for the Guinness brewery, it was the first steel framed building in the British Isles, based on the Chicago school of design structures, which became the basis for all skyscrapers. However, while in most such buildings, walls and plaster hide the structure, the Storehouse—all five floors of it—has few interior walls so the steel skeleton is visible from floor to roof, in all its revolutionary glory. The central core of the building is designed like a giant pint of Guinness with the head on the top—the spectacular circular glass wall Gravity Bar where the visitor ends his journey with a complimentary pint in hand and a spectacular view over the entire city. At night when the bar is lit up, a golden glow rises above the skyline like the creamy froth on top of the glass. The most important single object in the place, however, is in a small glass case sunk into the floor of the lobby next to the gift shop. This is the resting place of the original lease which the 34-year-old Arthur Guinness, founder of the family, signed in 1759.

Guinness postcard | With 100 pounds sterling in cash left to him in the will of the Archbishop of Cashel, Guinness acquired the disused St James Gate Brewery on four acres in the center of the city , a property for which he and his descendants would pay 45 pounds a year (today around $68) for the next 9,000 years. Shrewd fellow that Guinness: The lease still holds which perhaps explains how the history of the Guinness Brewery came to be virtually the history of Dublin itself. At the time of the purchase there were some 200 breweries in Dublin—20 of them in one street. Arthur set out to get rid of his rivals so that today there is but one other “stout” made in Dublin—Murphys—which may be a favorite local brew but doesn’t begin to compete on an international level with Guinness. By the 1770s Arthur, who up until then had been brewing ale, began to experiment with a ‘porter’ given its rich dark color by the inclusion of roasted barley. Dubliners responded to the new libation like their dray horses to hay, and by the end of the ‘70s Arthur had given up brewing ale completely. Today 4 million pints of Guinness a day leave the brewery and are shipped to more than 150 countries. As with most of the things that make one happy in life, the ingredients are simple: Barley from local Irish farmers, which connects Guinness directly to the barley drink of the ancient Irish Celts who staved off the cold winter nights with a brew called “coirm.” Where we stayed

We flew into Shannon from Los Angeles

on Aer Lingus and rented our car from

Murrays at the airport. There were eight in our party all from

Ventura County—so other than our two

nights in Dublin where we stayed in a

local hotel (The Georgian Hotel,

l8 Lower Baggett Street, in the heart of

Dublin which cost $125.00 a night) - our

group rented two separate houses in

two different parts of Ireland:

The first was a wonderful four bedroom

spot called Garanfada House on

Lough Ine in County Tipperary. In

October the fully furnished house—which

also had a working computer with

Internet access—cost us just over 800

dollars for the week! A fantastic rental.

Rates are higher in season. For details

email the owner Joceyln Waller at

Jwaller53@aol.com. The second house was further south in

Skibbereen West Cork: A magnificent five

bedroom Victorian house on the gorgeous

Lough Ine a famous local beauty spot.

The house in October was around $1,500

for the week—and higher during season.

Email Irene Beard at Irene@irbeard.net. For a wide selection of hotels or

self-catering houses or cottages contact

Irish Tourist Board, 345 Park Avenue,

l7th floor, New York NY 10154. Phone

(800) 223-6470 or (212) 418-0800.

www.TourismIreland.com. | The rest of the world was considerably less enthusiastic about the libation than the locals. The Greek physician Dioscorides complained that coirm “being drunk by the Irish instead of wine produces headaches, is a compound of bad juices and does harm to the muscles.” The second important ingredient is the hop, which adds the distinctive beer smell and the characteristic bitterness of stout. The third vital ingredient is yeast, which is responsible for that creamy head. Finally comes the water. Rumor has always had it that Guinness is made with water from the River Liffey which flows turgidly and decidedly unsanitary through the City of Dublin. Happily it isn’t so. In 1773 the Dublin Corporation (Council) finally woke up to the fact that Guinness was siphoning off the lion’s share of the city’s water supply and demanded payment. But Guinness’ lease provided him a water supply “free of tax or pipe money” and Arthur refused to pay. When the City’s Sheriff arrived to block his water, Arthur grabbed a pickaxe and declared according to reports: “with very much improper language that they not proceed.” Agreement was reached and the water supply was assured. Eventually even that supply was insufficient and Guinness began to pipe water directly from the Dublin mountains. The process by which the raw barley is turned into malt, combined with the roasted barley for color, mashed with hot water, into a porridge-like sludge, the liquid of which is then drained, added to the hops and fermented with yeast to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide gas, to become stout, is laid out in the Stonehouse for 500,000 visitors a year to marvel at. Beyond Ireland’s borders, 10 million gallons of Guinness are enjoyed everyday. Guinness is actually brewed today in more than 50 countries including Nigeria, Malaysia, the Cameroons and Ghana. The company employs 800 people in its Dublin operations, 15,000 throughout Ireland and an inestimable number worldwide. Guinness devotees have extolled its virtues through the ages. One of the Duke of Wellington’s officers, badly wounded at the Battle of Waterloo, confessed in his diary, “When I was sufficiently recovered to be permitted to take nourishment, I felt the most extraordinary desire for a glass of Guinness. I am confident that it contributed more than anything to my recovery.”

Guinness Storehouse | Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli wrote to his sister in 1837, “ I dined, or rather supped at the Carlton with a large party, off oysters, Guinness and broiled bones.” And during the Crimean war of 1854 it was reported in the press that “a vessel has been chartered to convey 500 hogshead of Messrs Guinness’s porter to Constantinople direct.” Not only do they make great stout, but Guinness is famous for its innovative advertising. Artist John Gilroy from the 1930s well into the ‘60s used animal cartoon characters from seals to lions to the most famous of all—the Guinness Toucan—in his “Guinness is good for you” campaign . His original concept featured a pelican with seven glasses of Guinness balanced on its beak and the rhyme: A wonderful bird is the pelican Its bill can hold more than its belly can It can hold in its beak Enough for a week I simply don’t know how the hell he can. In the interests of temperance and taste, the mystery novelist Dorothy L Sayers changed the bird to a toucan, cut the number of glasses to two and the rhyme became: If he can say as you can Guinness is good for you How grand to be a Toucan Just think what Toucan do As children it was impossible to escape the face of Guinness. Wherever you traveled the animals and the smiling face carved in the head of the pint gazed down at you from the sides of buses, trains and buildings. Today Guinness’ ad men pride themselves on capturing the zeitgeist whether they’re pitching their product in Africa or Micronesia. The ads work. On the fourth floor of the Stonehouse, a wall full of message boards carry paeans of praise from grateful consumers from around the world. Herewith a small sampling: Plane ticket to Dublin: 1200 Euros Bus ride to hotel: 10 Euros Hotel stay in Dublin: 600 Euros A pint of Guinness at the Factory: Priceless! And the following sad, and alas all too typical Irish lament: “Di Loves Kevin Shaw. Alas, Kevin loves Guinness more.” Which leaves only one question: Is Guinness really good for you? Is it more than just a clever ad campaign? Well it turns out a pint of Guinness contains virtually all the B vitamins, plus zinc, potassium, calcium and iron. Quod erat demonstradum. Some legends at least do not disappoint. Check out the Guinness website: www.guinness-storehouse.com. |